The Dust of Childhood

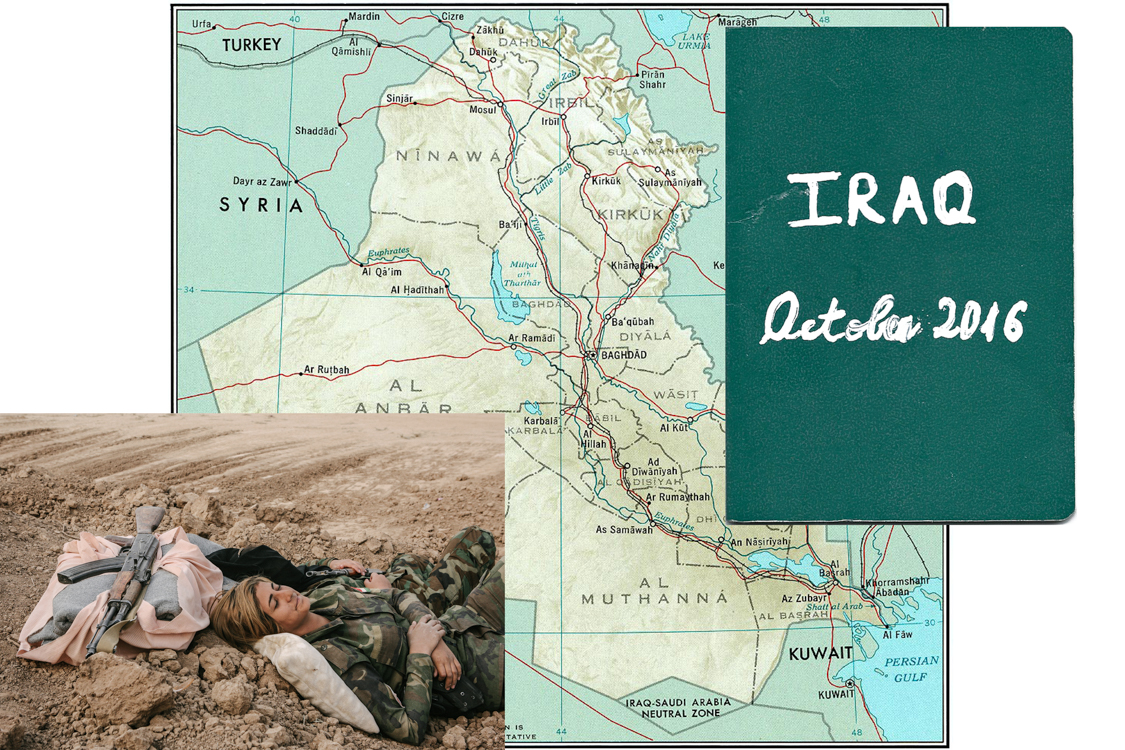

Iraq, 2015-2017

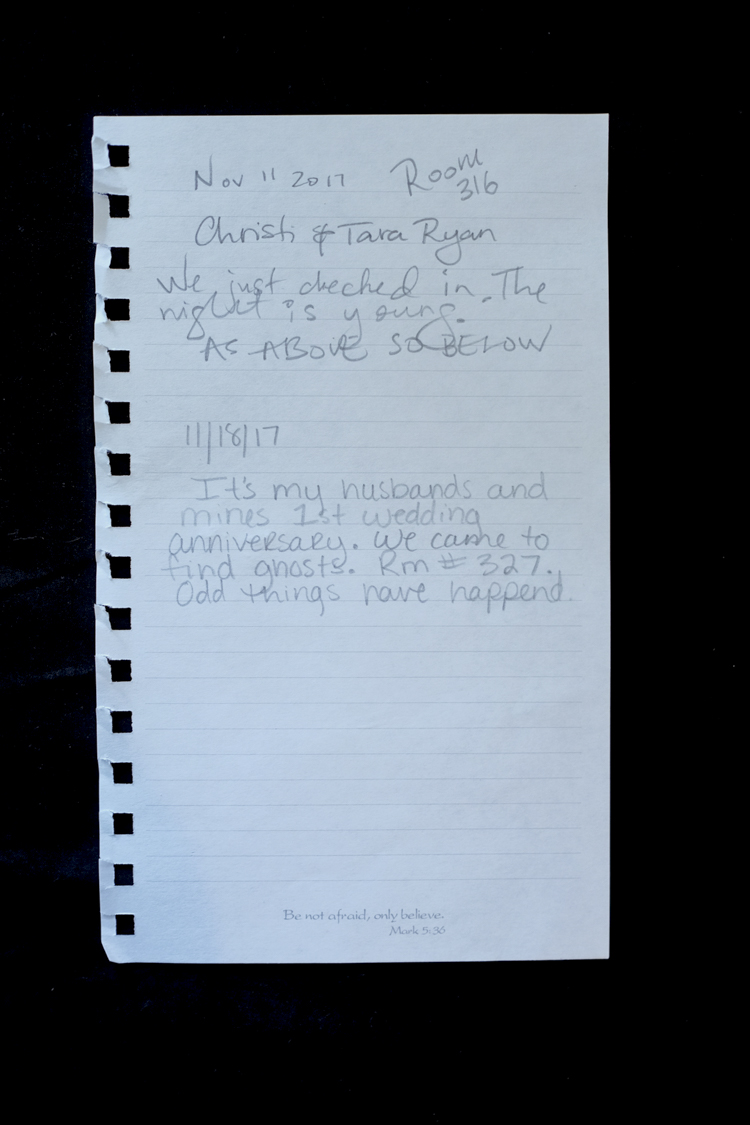

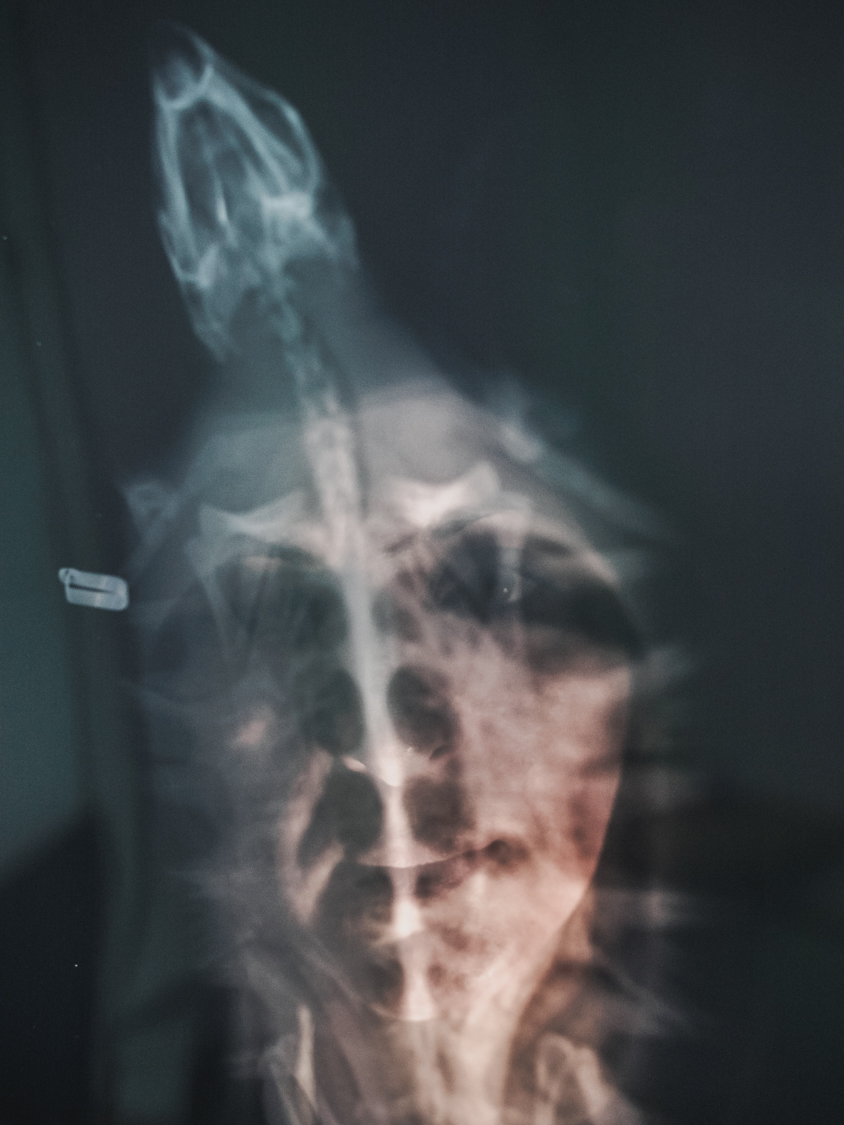

She bore the name of a flower: Gulchin. Her real name being Munire Mina. She had left Iran at the age of 15. She is now in the Sinjar Mountains where time seems suspended in the ruins since the August 2014 massacres on the Yazidi community. In her party, love and sexual relationships are forbidden. Some women have secret abortions. Men and women seem frozen in an abandoned setting, their stares lost towards death. Munire Mina died in 2016. She stepped on a mine. She was 23.

Like Munire, many other young underage girls have left their family for serving a party. They all dream of a new future with a good life by becoming a soldier. On Bashiqa front line, near Mosul, the teenagers from Iran who look like children are carrying cuddly toys and rifles. When asked if they are minors, the leader of their party, responds with embarrassment: “This generation is like that, their faces do not show their true age.”

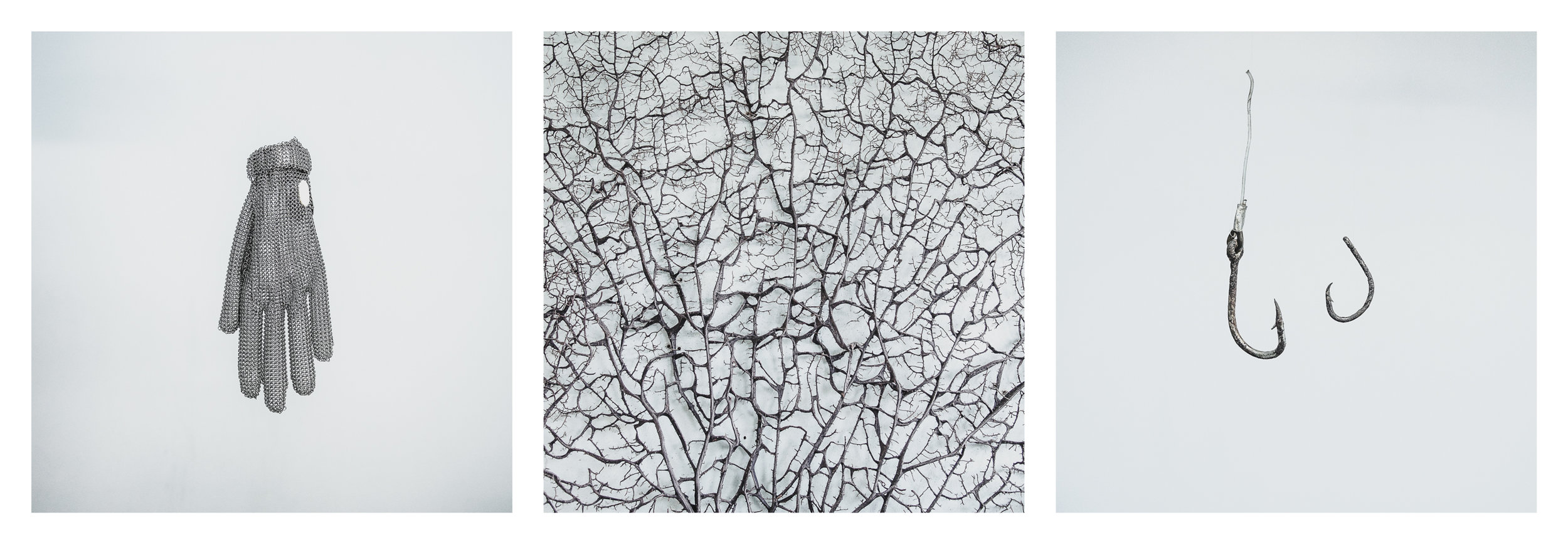

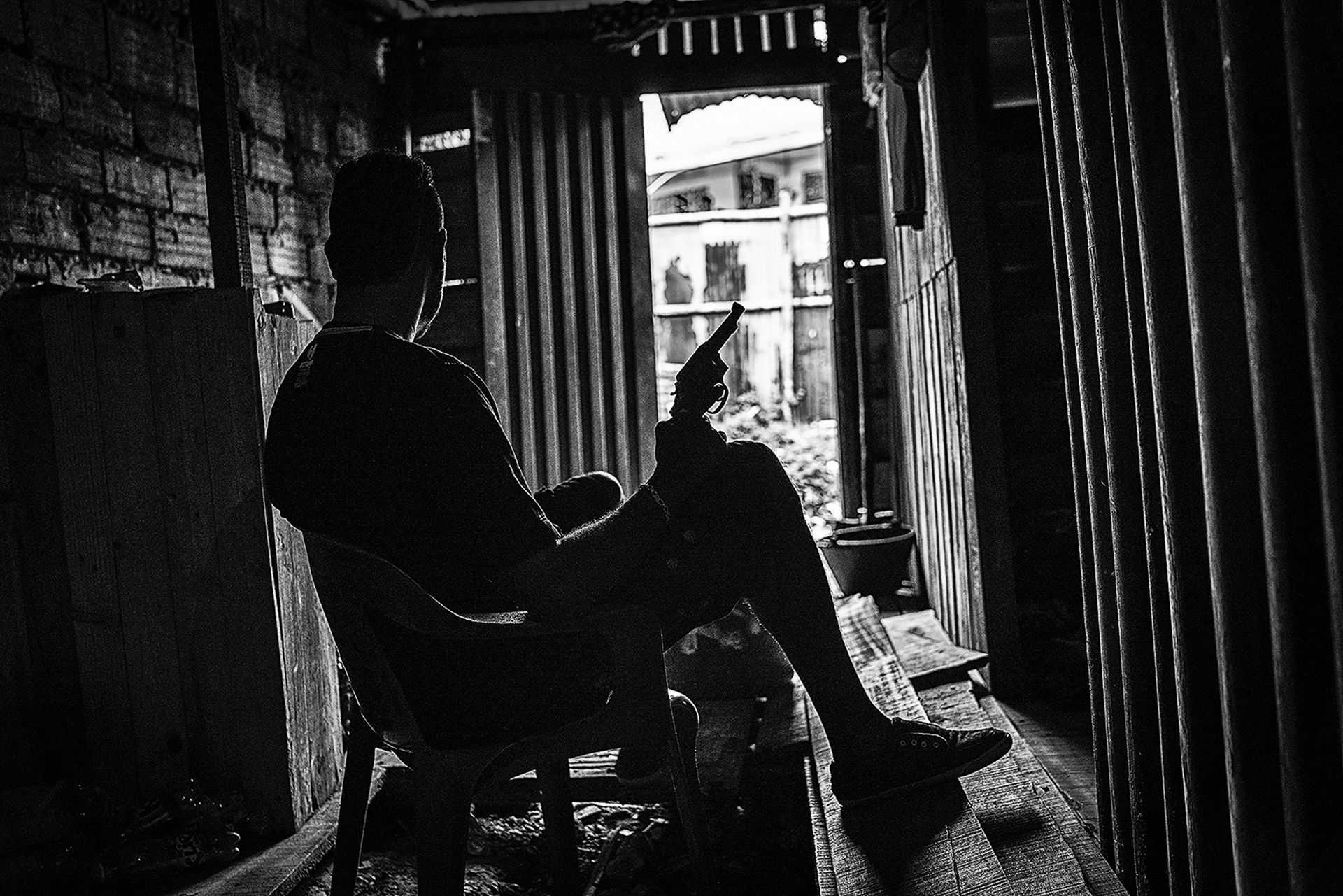

These young soldiers are often put forward as valorous warriors by their party for their propaganda – an image enthusiastically forwarded by western media. They are illustrated in an entirely different reality. Far from the war staged for the media and its subsequent treatment of violence, the conflict is looming. Immersed in this war, the young recruits feel that they are embodying this image of strong, independent woman who has been sold to them. However, the leader perpetuates the patriarchal aspect that had caused them to flee their homes in Iran: instead of being at home to take care of household tasks, they fill sacks of earth to reinforce the lines that only men will cross. So what do these girls, who fight Daesh with AK-47s marked “Mama I love you”, do in this Mosul offensive? Naim has long black tightly attached hair and a wise and reserved child’s face. She said she is 18 but looks 13. Naim is a few kilometers from Mosul. She runs to a forgotten toy, a white plastic house with a coral roof – a childhood lost too early.

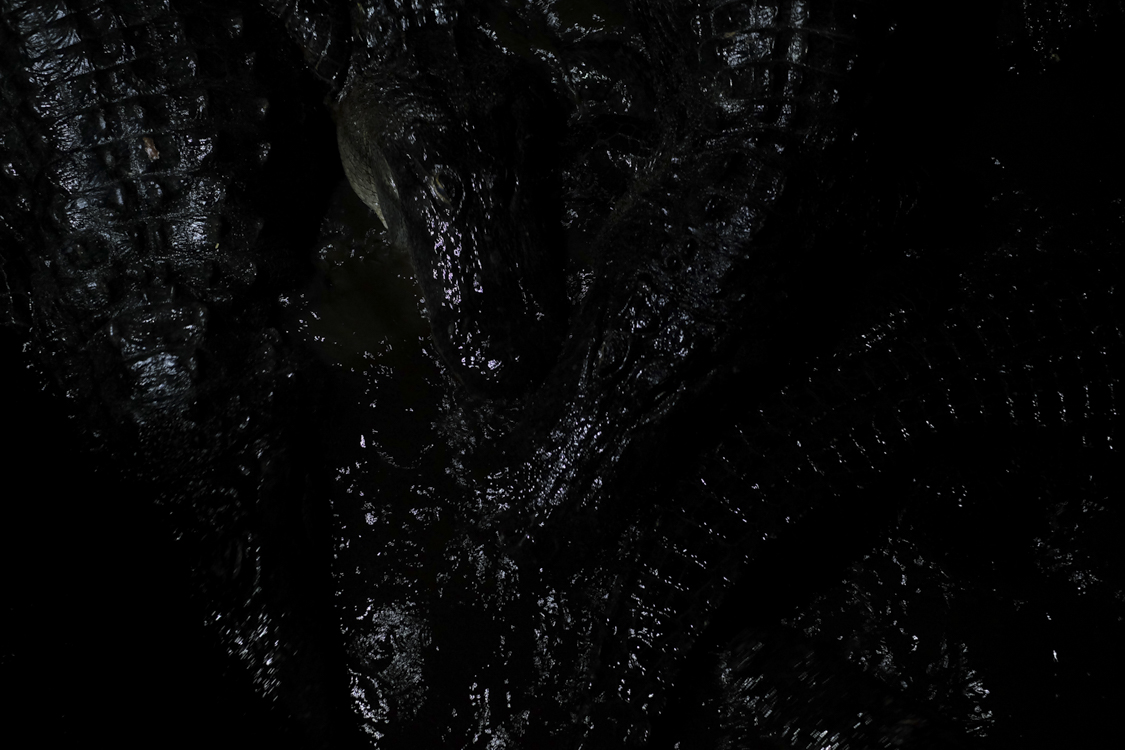

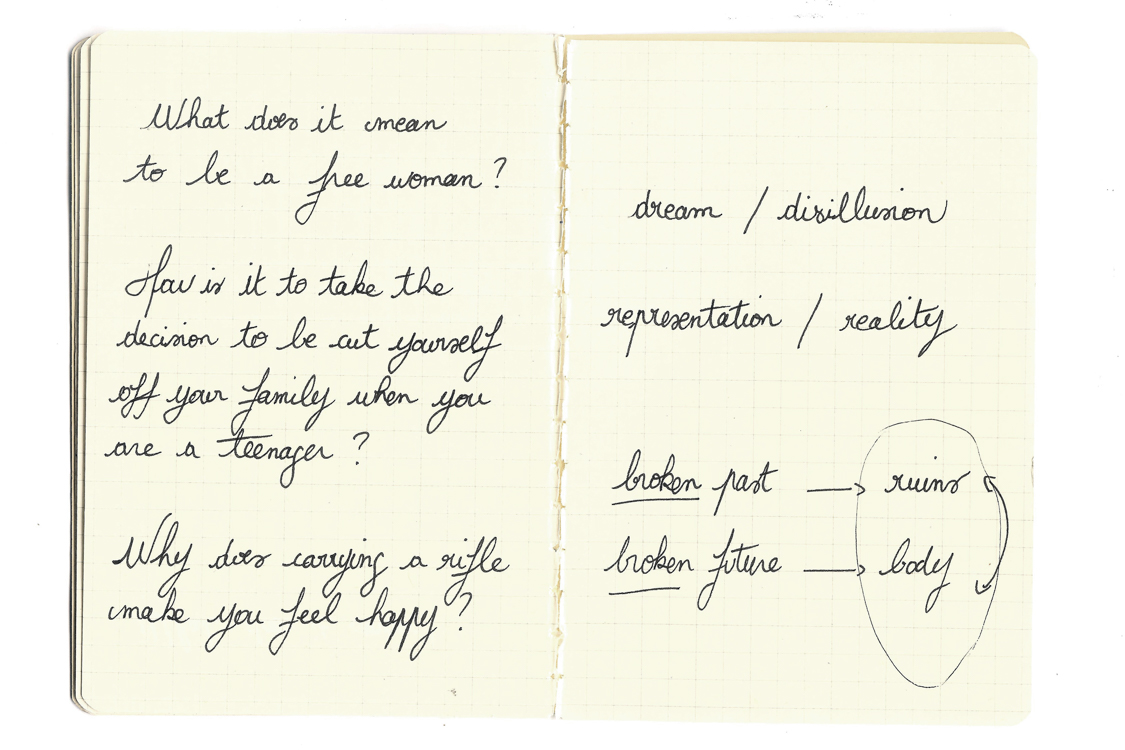

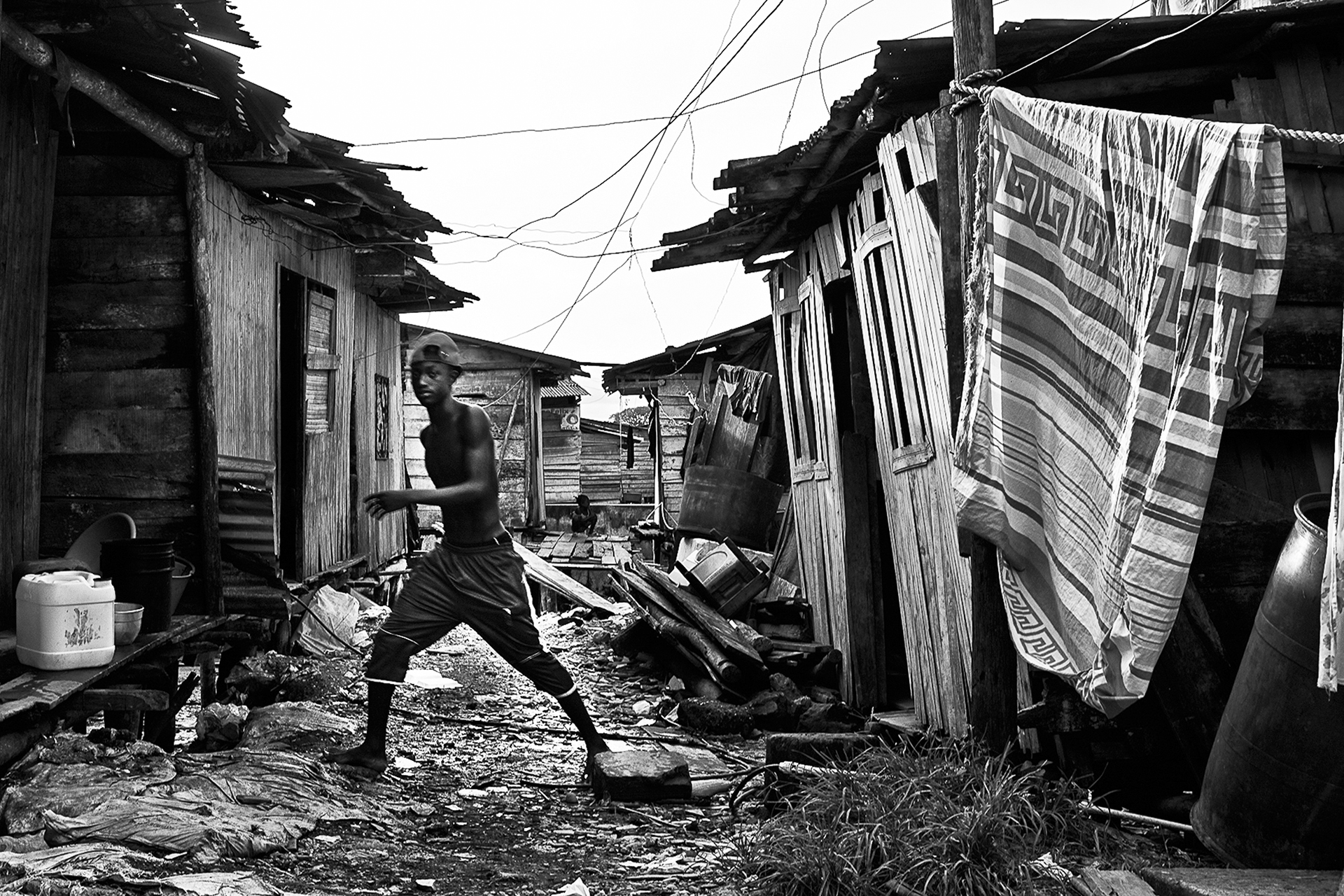

Through this ongoing work, I am questioning about the duality between dream and disillusion, representation and reality but also the propaganda on young girls. I am creating a dust atmosphere: broken human existence in ruins, something slow towards death or a form of freedom in the immensity of the suspended time.

Lea Mandana

Lea Mandana is a documentary photographer and a reporter.

She grew up with two cultures: French and Iranian. She became an architect in Paris where she focused her studies on the link between ruins and the imaginary.

Between 2015 and 2017, she covered Iraq, including the Mosul offensive. Her interest is in women in violence and war. Her sensitivity comes from her personal story and cinema. She likes to use writing, photography and collaboration with her subjects for creating an atmosphere in her narrative. Ideal and disillusion, irony of paradoxes, strength from fragility/injury are recurring themes in her work.

She has worked on assignments for The New York Times, Libération, Grazia, Le Monde des Religions (Le Monde) and has been published by United Nations University, Fisheye Magazine, La Croix, Mediapart, Bloomberg Businessweek, amongst others.